Situational and Composition Photography Tips For Wildlife Photographers

Patience

I hear the comment all the time. “How long did you have to wait to get that shot? You must be really patient.” I am patient. But to be honest, I am rarely when it comes to my photography. Maybe I should be more patient when it comes to taking photos. It's just not in my DNA. I will never be the photographer that sits in a blind all day waiting to get the shot of a loon chick on a mom's back in the perfect photographic setting in the reeds.

I prefer to keep quietly moving and observe wildlife behavior in an area that I am in. When coupled with my previsualization research I look for vantage points that I want to be photographing from to help me be better prepared to get the shots I want. My method also allows me to see more of the area, appreciate the beauty of nature, and often offers me the opportunity to photograph other local species as I move around.

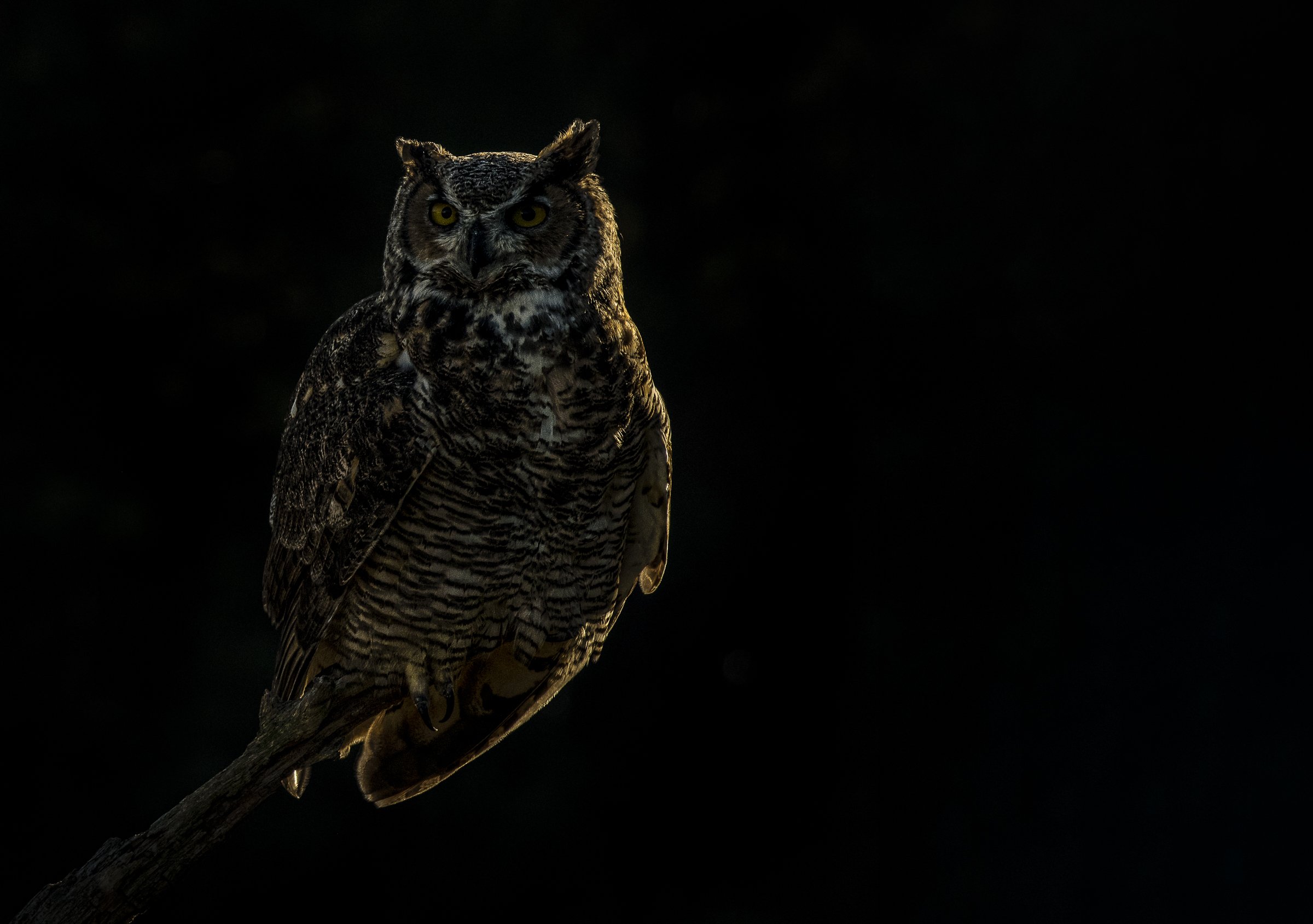

I identified the field where this owl was frequently hanging out in the morning light. I wanted a photo with some rim lighting. I made sure i was there before first light on multiple days. I just had to be patient and wait for the owl to be in the right position when the morning light caught the owl from the horizontal position I wanted.

You will often find me GPS marking locations as I move around. As I mark these locations I am checking available light at these vantage points. I always pay attention to light and how it illuminates a scene (more on this later). This method will allow me to be ready to use the lighting to create more impactful images.

I will make several return visits to the same location to observe the wildlife patterns. You will be surprised how habitual an animal is in its environment. Hunting the same areas at the same time of day, using the same areas to rest in. This method has served me well over the years. It might work for you, but then again, you just might have more patience than me and be happy to sit in that blind waiting for the perfect moment.

Composition

Composition is probably the most important creative element in your photo. Without a good composition, Your image will not have a visual appeal. There are some basic composition rules that will instantly make your photos better. Once you apply these basic composition guidelines you will be able to go to the next level and start to master wildlife storytelling.

Here are a few basic composition guidelines which will make your composition much more appealing in almost any situation.

Shooting wildlife at eye level – Doing this makes the person looking at your image feel like they were right there with you while you took the photo. It also separates your images from other photographers that took a photo just standing and looking at the wildlife. Not all wildlife photos should be at eye level, but it is certainly a composition that makes you feel connected to your subject.

The rule of thirds – The rule of thirds is part of a more fundamental visual aesthetic called the Golden mean. This ratio is found throughout nature, music, the visual arts, even the human body, and in patterns of behavior. The 1 to 1.618 ratio is accepted as a principle of good design and has been employed by designers going back as far as 300 B.C. when Euclid mentioned the golden mean in his writing of Euclid's elements

As it applies to photography, the rule of thirds states that when an image frame is divided up into three equal segments, both horizontally and vertically (think like a tic tac toe board) there is an aesthetic value in placing important visual elements on one of the horizontal or vertical lines, or when two of these lines intersect.

1 – The images focal point

2 – The primary wildlife subject

3 – The horizon

The intersection of where the horizontal and vertical lines meet is called PowerPoint, and it's a good place to start when trying to decide where to place your wildlife subject and focal points. If you're working the wide environmental wildlife scene, try placing the subject on one of the intersecting points. it's a wildlife headshot, place the eyes or prominent facial features 1/3 of the way from the edge of the frame. If there's a horizon between land and sky or water and land, try placing the Horizon 1/3 from the top or ⅓ from the bottom.

Just remember, if you follow the rule of thirds consistently, your wildlife images can quickly become boring and predictable. The greatest virtue of the rule of thirds is in helping you decide where to place your subject within the image frame. It's a good place to start, but if it doesn't work, you can try something else.

Use the rule of thirds as a guide when you're unsure where to start, but sometimes, breaking the rule is a better option. Exceptions to the rules are often the most visually engaging photos but don't break it just for the sake of breaking it, break it because it's better. What’s better? Well. that is up for you to decide, after all, art is an expression of your own personal vision.

Using Negative Space In Your Images – Negative space is the area that surrounds the main subject in an image. In this context, the main subject, or animal, can be referred to as positive space. Just as important as the main subject itself and its positive space, the negative space helps to define the boundaries of the positive space and brings essential balance to any image.

In layman's terms, negative space is the “ breathing room” around your wildlife subject that determines how balanced and pleasing the eye image looks and feels. negative space helps emphasize the primary subjects in the photo, which naturally draws the eye of the viewer. If there is not enough negative space around your animal, it may appear cramped and crowded by the image frame. If you allow for too much space around your subject and it feels out of balance.

Mozart once said that music was not only about the notes of themselves but the silence between the notes. This is also true with the negative and positive space in photographs. A good exercise on the art of creative visualization is learning to ignore the primary visual element in the scene and instead concentrate on the gaps and empty spaces between them. This forces you to pay more attention to the negative space, where the negative space is, and how it relates to the main subject or subjects in your photograph. In turn, this will help you see lines, shapes, and areas of visual weight much more clearly, And how they relate to each other and the image frame itself.

When it comes to space and spacing in general, you usually want to leave enough room between the important elements so they don't merge together. Let's say you have a group or herd of animals in a photograph – You want to compose the scene so there are some empty spaces between each of them. The space has become as much a part of the pattern as the animals themselves. This is also true with regard to silhouettes, where any merging between important elements could destroy the integrity of the subject's shape or shapes.

Professional wildlife photographers know and understand that the image background is every bit as important as the subject itself. Wildlife photos with distracting or mess backgrounds lose visual impact by having the primary subject blend into or get lost in the background distractions. Make sure the negative space around your primary subject is ample. It will not feel cramped, and you will minimize any unwanted tangents in your image.

Focus on the eyes – Anytime you greet someone new, you shake their hand and look them in the eyes. Wildlife photography is no different. You’re not going to reach out and shake the lion's hand, but you are going to look them in the eyes, just as someone does when looking at the photo you take.

Biologically, we humans have a visual system that is hardwired to immediately train on an animal's or fellow human eyes. Whether it's a portrait of wildlife or a person, the eyes are the initial focal point in the image and where the viewer's attention is first drawn too. The viewer of your image will immediately lose interest if the eyes are out of focus, or are blurry.

During the capture, if the eyes are clearly visible through the viewfinder you want to position one of the camera's focus points directly on the eye, or the eyes. If the animal or bird is looking 90° to one side and the focus plane of the face is approximately 90 degrees from the angle of the camera and lens, everything should be reasonably sharp even at f4 or f5.6.

But, if the animal has a long snout or a bird has a long beak, or it's looking directly into the camera, the nose or beak could be unsharp when you focus on the eyes. In this case, you should stop down your lens to f11 or f13 to get all of the face and focus. But then again you might like a shallow depth of field and selectively focus on only the eyes. If the face or body of the animals is only partially in focus, the image will still work as long as the eyes are Sharp.

When the animal makes eye contact with the lens and camera, it becomes easier for the viewer of the image to make a connection with your subject. That connection will only happen when the eyes are sharp. That said, even if an animal is looking in a different direction, the eye or eyes must still be tack sharp for the photo to pass your litmus test.

In portrait photography, you may often hear, “The eyes are the window to the soul”. I want you to begin to think about an animal’s eyes the same way. Eyes show an animal's fear, sadness, anger, and even happiness, and if you can capture that emotion, your viewer is going to have a positive reaction to your photograph.

Portrait Versus Environmental Photo – Depending on your distance from the subject, you can choose to create a portrait or shoot it along with the environment it is in. Both options can create an impactful image. But the decision is often based on light, backgrounds, and other items visible in your viewfinder. If there is good light on your subject and not on the background try a portrait. If the background is amazing and compliments your subject, It is always preferable to try both in the moment, and take a look at them on your computer monitor.

Do not cut off body parts unless it's intentional – This is so easy to do. We get so fixated on the body or face of the animal, we forget about the tail, feet, or wings as a bird is flying.

I often take a quick scan in my viewfinder to watch to make sure I am not cutting any body part off in the frame. Eliminating this could be as easy as photographing the animal a little wider and cropping it to the desired composition in the editing phase.

Avoid Tangencies – The word tangent usually indicates that two things are touching, but in photography, the term describes shapes that touch in a way that is visually bothersome. When creating a composition, there are so many different things to juggle that it's easy to miss even the obvious flaws—and that's when unwanted tangents sneak in.

The main, distracting tangent here is that blade of grass that goes from the rock to the Arctic Fox’s head. There are others as well… the blades of grass that reach to the top of the image frame are also distracting.

As I mentioned in the previous composition tip I often take a quick scan in my viewfinder to watch for tangents. Eliminating them could be as easy as moving to another vantage point

Wildlife photography composition has so many little things to remember. But the more you practice, the more you will subconsciously pay attention to them without thinking about it.

Unusual perspectives

Wildlife composition usually involves capturing the whole animal in action. They may be running, hunting, fighting or flying and the typical goal is to capture that action.

However, don’t ignore interesting close-ups of intricate details. Maybe it's the scales or an alligator, the horns of a bison or the claws of the lizard. Your camera can provide a window into these details that a viewer wouldn’t normally appreciate.

Backgrounds

Wildlife photos can be ruined because the backgrounds are cluttered, distracting to the viewer, or just plain ugly. An example, black bears on a seashore can be beautiful… black bears at the local dump just seem wrong. It is just far less natural and not inspirational.

A general rule to follow… “Anything that does not make my photo better makes it worse.”

This does not mean you can’t take a good wildlife photo at the zoo. You just need to manage the setting. A good tip to remember is the following. If your background is spoiling your shot, zoom right in on the subject to eliminate as much of the background as possible.

By zooming in, you will also reduce the depth of field to a minimum, so any background that does appear in your photo will be out of focus and less distracting.

On the flip side, a wildlife photograph that captures the subject in a beautiful natural setting can be even more effective than a simple close-up. This is my preferred way to take a wildlife photo. My inspiration comes from the paintings of Robert Bateman, a fellow Canadian.

Robert pays less attention to the detail of the animal and pays more attention to form, light, and space. His ability to create a painting that conveys a sense of place for the animal is inspiring to me. His use of negative space and the indigenous flora and fauna to convey a sense of space allows him to create images that I find appealing. Robert also uses neutral tones in his art. He holds back extreme whites and blacks in his paintings, and only uses these extremes when he wants the eye to focus. I identified with that aspect of his images, and you can see that inspiration in many of my images.

Let’s look at an image I took. I want to use a few examples to help you better understand how I approach backgrounds. How Robert inspired me, and how my style was born out of my inspiration for his work.

This is one of my all-time favorite images by Robert Bateman. During a trip to the Great Bear Rainforest I was in a very similar setting. I could have easily created an image identical to his. Instead, I chose to create my version of a black bear coming out of the darkness.

Wildlife and Bird Positioning

How you choose to photograph wildlife is based on personal preference. You may like animal portrait images, maybe lots of action. Each has its merits. But it is the subtleties of an animal's movement and the story that you tell that will separate your photos from others. How the paws or hooves are positioned. How is the head in relation to the body? Is movement being introduced in your image? What feathers are predominantly displayed? Are there distracting tangents? Is there an interaction between multiple animals? How do you showcase the environment the animal is in?

We have gathered together a sample of wildlife and bird images in order to allow you to compare body and wing positioning to help you begin to understand your personal preference and learn to tell a better story with your wildlife images. While you are looking through these images we are also going to point out some of the subtleties that we watch for in our own wildlife images.

Our first set of images was taken on a workshop in Nunavut Canada. We traveled by plane to a remote lodge hundreds of miles from civilization where the tree line ends and the sprawling tundra and eskers form south of the arctic circle.

Here is a photo of a Caribou grazing in the tree line. His head down. You cannot see his eyes and the hooves are hidden behind the mound. If this is the only image you could get on your trip, it will suffice. But it really doesn't showcase the animal or the glorious landscapes we were in.

Here is a better image. Notice that the head is up on this caribou, the antlers are on full display and the caribou is looking off into the distance. It's a great portrait photo that shows off the colorful ground cover in Northern Canada.

Here is an even better image of a Caribou in movement as it walks through the Tundra. The photo was taken as one of the hooves is visible. This shows motion. The rest of the hooves are also not behind a mound like they were in a previous photo. This caribou was photographed because antlers have lost their velvet and visible blood covers them. It helps tell a story that the Caribou was photographed in the fall when they are entering the rut before winter. The head of the Caribou is elevated and in a relaxed state, and the eye is visible. There is the perception of movement in this image, and the animal is placed nicely in its environment.

Then we have these two photos of two animals in the same frame. One of two Caribou standing there in a beautiful autumn setting in Northern Canada. Both Caribou are looking at the camera. The Caribou is in a gorgeous setting of fall colors, and both are in focus. While one caribou is great, two caribou can be even better. The second photo is of two wild Musk Ox that is standing in a beautiful scene. While one animal is great, two might just be better

You see, there are little idiosyncrasies that elevate the aesthetic appeal of your photography. Head positioning, leg position, clarity of the eye, more than one animal, even the setting can make your image more appealing to the viewer. Watch for the little things. It will create a better image.

Here is a list of quick things to think about when photographing animals.

Elevated head versus feeding

Walking or running with one or more hooves or paws elevated

Are they making eye contact with me? Is there catch light?

Elevated action images like hunting or interaction with others.

Are they doing something humorous?

Adult interaction with young

Here are a few things that I try and avoid.

Do they look stressed? Are their eyes open wider than normal, ears turned forward, maybe their heads are slightly lower than normal. – these are things to try and avoid.

Here is a series of images of a Bald Eagle to show different body and head positioning for you to consider. These images were taken during one of the largest convergences of migratory bald eagles in North America. Thousands of bald eagles migrate to this area to feed on the spawning salmon while they mate in the November/December time frame.

In the first image, we see a bald eagle hovering in the sky. A nice portrait. But it does not tell a story. This image could have been taken at any number of locations throughout North America.

Then we have an image of a bald eagle walking along the shores of the river. It puts the eagle in the location of the river, and experienced wildlife photographers would assume it is at a river to feed. There is good contact with the eyes, The white if the head is not blown out and you can see the details in the feathers. Even the feet are visible.

Here we have a bird in flight. Notice the photo was taken as the wings were stretched to show off the primary feathers, still maintaining contact with the eye. You can also see good detail in the tail feathers. This is a pleasing bird in flight right above the river showing off all the details a viewer would want to see.

Now we introduce the action. A photo of two mature eagles and a photo of an immature bald eagle is challenging a mature bald eagle for the carcass of a salmon. This photo elevates to telling the complete story of bald eagles being at a location during a salmon run. It also shows how eagles interact with each other when a food source is present.

Between both eagles, all the important elements are on display. Wing detail, talons, even the setting of being on a river is shown in this image because the point of view is so low to the ground.

Here is a list of things I look for when photographing birds

Are the wings on full display when in flight? I like or showcase the primary feathers and tails.

Are they making eye contact with me? Do you have catch light present in the eye?

Elevated action images like hunting or interaction with others.

Are they doing something humorous?

Adult interaction with young

Here are a few things that I try and avoid.

Do they look stressed?

Tangents like branches sticking out of their bodies

Do not Sacrifice Safety for a Photo

I think stating the obvious is a good way to start this section. Wildlife is wild. As such they are unpredictable. But that is not the only thing that we need to be cognizant of. You could be far away from civilization, and let’s face it, more than likely out of cell range, and not walking on paved roads. Both the terrain and the creepy crawlies that inhabit the areas you may visit can cause serious, even lethal injuries.

The first bit of advice I would give you is to try not to go out on your own. Take a buddy. I know that is always not possible. But I highly recommend it. My second bit of advice is to have something like an inReach Mini. I discuss that product a little later as one of the accessories we usually take with us when headed out into nature.

Be Respectful of Your Subject

As photographers, it is important to respect all wildlife. The long and short of it is to just use common sense. If you think that you are putting wildlife, or its natural habitat in danger stop what you’re doing and look for an alternative method to acquire the photo.

Here are four categories that I would consider detrimental to wildlife.

Baiting or Feeding - This is often done with food that is not natural to their diet. Human food can be harmful to an animal looking for a free meal. It also habituates the animal to humans. If they view humans as a free meal they might put themselves in harm’s way on roadways or residential areas.

Destroying habitat – Try and practice a “leave no trace” method of being out in nature. When you leave, there should be little trace that you were there. That goes for vehicles. Don’t blaze a trail out into the wilderness and destroy habitat. Park in a safe area and walk in.

Crowding Wildlife – This tactic not only stresses the animal but also impacts the animal’s natural way of life like mating, raising young and hunting.

Provoking animals for movement – This is one of the worst ways to capture a picture of an animal. There is no excuse for putting an animal under such duress in order to take a photo. Wildlife lives on the edge of life and death. They move only when they have to and feed only when necessary. Provocation puts a strain on the wildlife that just isn't necessary.

Lighting in your image

We have discussed the importance of focusing on, and positioning of your subjects But light can transform a dull image into a brilliant one. Light needs to be used wisely depending on the type of light present, the intensity of light, the direction of light, and the time of the day.

Here are some common lighting situations that could help you create compelling shots.

Backlighting happens when the light source is behind the subject – for example, light during the golden hour when the sun is lower in the sky almost closer to the horizon. Window light indoors can also be used to naturally backlight a subject indoors.

This means that the light is directly in front of the camera, with the subject in between. This light can most of the time create a silhouette with a hazy feel and not many details on the subject, depending on the intensity and atmosphere present. You will also have some long shadows that can create a dramatic effect in the image.

Rim Light occurs if backlight is slightly moved (or the photographer moves to an angle when it is natural light) to fall from an angle, then this will show details of the subject instead of a silhouette and will have a rim light. Silhouettes also will have a rim light when light is used effectively, but the details in the subject will be lost with a lot of highlights showing up in the edges.

Rim light can beautifully light the edges of your subject separating the subject from the background.

Front Lighting occurs when the light is right in front of the subject, it is easier to photograph, but if the light is directly in front of the subject, it may result in a “flat” photo. “Flat” lighting is light that evenly spreads on the subject and is not at all the desired one for portraits. I try to avoid this because it makes a photo lo I ok two-dimensional; it is the shadows in a photo that create a three-dimensional effect.

Light from above of course is quite common. When you travel, mostly the sun is your light source, and most of the day the sun is right above your subjects. So it’s important to know how the light from above will affect your images, and what you can do to minimize the shadows that the sun from above will invariably create in your subjects.

Early mornings and late afternoons are great because the sunlight is more orange; the angle of the light is also more from the side, especially at sunrise and sunset. But also in the hours right after sunrise and the hours just before sunset, the light is not as harsh as in midday.

Side Lighting is arguably my favorite kind of light. Side light is light coming from the side – that is the left or right of the subject. It was used by the masters of painting—Rembrandt used side light in his paintings to give the picture a three-dimensional effect. When the light falls on one side of the subject, the other side is in shadow. The shadows are what give the picture a 3D look.

Like every skill, seeing the light—its direction and quality—takes practice. But with some basic knowledge of lighting situations, any person with a camera can “practice the right skill” and do what photographers do: stalk that light, capture it, and make it look fantastic.

Photographing in the snow

Our winter wildlife photography workshops us in locations with lots of snow on the ground. This often presents a new issue that most people have not had to deal with – how to get good exposure in a completely white scene without continuously messing around with shutter speeds, aperture, ISO, and exposure compensation.

To set exposure in the snow we usually just fill the frame with snow, and adjust the settings in Manual mode, until we see the peak on the camera’s meter indicate that the exposure is now at +2 stops for overcast snow or +1 stops for brightly lit snow.

Why is this something we have to worry about? Your camera sees a white scene. The computer in your camera is going to find 18% Grey and dull your image down. When it does this it gives your snow a grey or bluish tone that you don't want to have.

All camera systems are a bit different. Exposure compensation may work in Manual Mode in Nikon, but it does not work on a Canon of Sony. You have to be in Aperture or Shutter Priority for Exposure compensation to be used on a Canon or Sony.

Alternatively, you can adjust any of the three other functions of the camera to overexposure. Slow your shutter speed, but risk motion blur, adjust aperture but risk losing the depth of field or increase your ISO to increase exposure.

The downside of increasing the amount of light in-camera versus in post-processing is that you do have to continually check your exposure, especially on a day of variable clouds. But we would rather get it right in camera and have less to worry about in post-processing.

Panning Photography

Here are a few tips we put together to hopefully take your keepers from one out of five-hundred to one out of one-hundred. Like a lot of photography, panning is a percentage game; one keeper out of one-hundred photos is not out of the ordinary. But, I promise that “one” is worth the effort!

Panning works when you move the camera in perfect synergy with the subject. It’s not enough to just swing the camera from side to side. You have to move it in perfect synch with your subject. Sounds easy, right? “HA, we say…”

Generally, it is easier to pan with a fast-moving subject than a slow one. Animals running sideways to you are great examples. They are moving fast enough that you can pan smoothly with their straight-line motion. People walking or casually jogging are almost impossible; they are too erratic and slow to get much blur, and it’s difficult to pan smoothly.

Whether you shoot in manual, shutter, or aperture priority, the object is the same. You don’t want the shutter speed to change while you are shooting.

Your subject must be in focus. You might like to switch focus to AI Servo mode (in Canons) or AF-C mode (in Nikons). In this mode, hold down your shutter halfway to lock focus on your subject. Without letting go of the shutter, start following your subject with your camera at the same speed. Your camera would automatically adjust focus. You can take several shots at once; the number of photos is dependent on your camera. For you birders, it’s the same principle, keep the focus on what you want to be in focus.

There is no “correct” shutter speed for panning. The longer the shutter speed, the more blurred the background will be, and the higher the probability your image you wanted in focus will blur. A long shutter speed will make your subject pop out from the background, and that is good. It becomes a balancing act. As a starting point, let’s go back to the example of the sprinters running across the picture. Try anything between 1/8 of a second and 1/60 of a second. Beyond 1/8 of a second, it’s really tough to get sharp. Above 1/60 of a second, the camera will probably stop too much action and ruin the effect. Except for faster moving objects like flying birds or jets. Then you might need 1/250 of a second for a bird and 1/500 of a second for the jet, and that brings us to our next problem.

A Fluid, smooth motion is the name of the game. No jerking, no rushing, and done without hesitation. The stance should have you face the subject that you want to focus on or sit on the ground to stop you from moving too much. You then rotate your shoulders to pick up your subject in the viewfinder. Start clicking the shutter before your subjects reach the ideal point and then keep shooting after they pass that point. Good follow-through is imperative. The best panning shooters go out and practice their movements.

There is no right or wrong way to produce the desired results… There are no set rules here to give you. But try it, have fun with it, experiment with camera motion.

Things do not always have to be totally in focus. This type of photography, in addition to showing the motion of an object, can be an artistic type of photography. Technically, you should not be able to have motion in a still photograph. This is a two-dimensional form of art. But the act of panning will force a person to look at the image more closely, and they will until they come to realize: “That’s not a blurry picture; that’s a young boy taking a photo of the dog he loves running in the backyard. That’s cute!”

Now go out, try this, and “pay it forward” so the next person can have their AHA! moment.

Motion Blur Photography

Often confused with Panning Photography, Motion Blur differs because you are not moving your camera. Instead, you are composing the scene in camera and allowing the wildlife to move through the image.

This method will freeze your background while the subject is allowed to blur. You’ll need a tripod for this technique. You will select a background with some stationary objects and visual interest, but not so much that it’ll compete with your subject.

Put your camera on Shutter Priority and set your shutter speed to anywhere between 1/30 of a second to 1/250th of a second, then adjust to a faster or slower speed as you review results.

Bare in mind that as you decrease your shutter speed, more light will reach your camera’s sensor. This can result in overexposed photos. Your picture will look washed out and will lose detail. To compensate for this you will need to adjust either the aperture upwards to f16, decrease your ISO, or use filters like a polarizer of light ND filter.

Just remember to keep the camera still while your subject moves within the frame and the end result will give the impression of a moving animal by introducing a pleasing blur.

Heat Distortion

Have you ever taken a photo with a long zoom lens where you thought your technique was perfect, only to come home and see an image that is mushy and seemingly out of focus?

This happened to us on numerous occasions. Two instances come to mind. One when photographing a Grizzly Bear in the early summer in Yellowstone, and the other time when photographing Caribou up in Nunavut in Canada over dissipating dew on a sunny autumn day

You’ve probably seen heat distortion on a hot summer day, where there are waves of heat rising from a road. Or perhaps you have seen it in the exhaust from a boat, train or airplane.

Years ago when I first came across it in my photos, I thought it was either something wrong with my technique or equipment, but no amount of fancy gear or flawless camera technique can fix photos ruined by heat distortion.

When Will Heat Distortion Occur?

Heat distortion is caused when light is refracted through air of differing densities. Hot air is less dense than cold air, so light waves are bent differently in hot versus cold air. The result is visible heat waves when there is a significant temperature difference between the ground and the air above it.

On a hot, sunny summer day, you will see this above the road, but it can occur on just about any landmass where the sun heats the ground to a temperature higher than the surrounding air such as an open field or beach.

Bodies of water can cause the exact same phenomenon when the water is either significantly warmer or colder than the air above it. A warm ocean with cold air above it may show heat distortion and so will a cold ocean with warmer air above it.

Heat distortion is not restricted to hot summer days. It can also occur in arctic temperatures during winter where the sun warms the land or mountainside to a temperature well above the air temperature.

The further away from the subject of your photograph, the more heat distortion will be present. The further distance means that the light is traveling through more air before it reaches you, therefore it gets refracted more in areas where heat distortion is present.

A long zoom lens usually means you are trying to photograph subjects at a greater distance. That greater distance increases the chance that heat distortion can ruin your images. Heat distortion is most prevalent at ground level.

Zoom lenses have the added disadvantage of bringing the detail of the heat waves closer, making the result larger and more obvious in your photo. Photographers who spend more than $10,000 on a monster 600 mm or 800 mm prime lens will want to remember this before getting angry and wanting to send the lens back for repairs.

How Can You Avoid Heat Distortion?

In many cases, heat distortion is unavoidable and there is nothing that you can do to fix it, but there are a few different ways to avoid it.

Move closer to your subject. Reducing the distance that light travels through the refracted air will reduce the amount of heat distortion that you see in photographs.

Avoid photographing over surfaces that are easily heated up by the sun, such as a road, beach or similar.

Shoot near sunrise before the ground has heated up or near sunset once the ground has begun to cool. There is less or no heat distortion during these times.

If photographing over a large body of water, try to take photos when the air temperature is similar to the water temperature.

Soft, out-of-focus images can be caused by poor technique or the wrong camera settings, but once you have ruled those out, don’t forget about heat distortion.

Don’t Photograph Too Tight

Almost every animal you will photograph has distinct characteristics, not to mention animals do not always stand still. Elephants have their long trunks that are often moving in different directions, peacocks have a beautiful tail that can open quite wide, Owls and Albatross have huge wingspans that can quickly get out of frame as they take to flight.

These characteristics are a major part of the animal’s personality and these elements are not ones you want to crop out of your image. Shoot wider than you think is necessary. The number of pixels in today's cameras will allow you to crop your image to the best composition in post-processing.

Pre-visualize images versus shooting on the fly

Pre-visualization comes from your research. You would have seen an image that you liked while doing your research, and something in the landscape you are in just piqued your interest. This would be an instance of exercising patience and waiting for an animal to walk into your scene before you take a photo.

The number of images you take in this method will be far less. The advantage is you will get that one or two keepers that you really wanted to get. You will also spend less time going through images you took while you took an image everywhere you saw an animal. The disadvantage of pre-visualizing an image, and waiting for the right moment is you can get so focused on one photo, you miss out on all the other possibilities that may present themselves.

Shooting on the fly is more about following the animal wherever it goes. You're going to take many more images this way, no doubt with many keepers after sorting through the hundreds or thousands of images you took

We suggest a mix of both strategies. You are probably on location more than one day, so alternate, get all the photos, pre-visualized, and the ones on the fly.

Photographing From a Blind

Shooting from a photographic blind can be very useful, particularly when photographing wildlife that is not used to seeing humans in their environment. I do not often use a blind, but there are definite situations where I do. – Photographing local birds – a local fox den – a known area where animals are known to use as transition areas – If you find a carcass in the wild.

Why Use a Blind? – Photographing wild animals is sometimes only achieved by using a blind to hide your presence. If you are not seen, heard or smelled by the subject, you have a good chance to capture behaviors that you wouldn’t otherwise see if they are aware of your presence.

Types of Blinds – Several types of blinds are available for use, including the permanent blind, the temporary blind you can set up using items found on site, and your own portable blind. Each type has its advantages and disadvantages.

The blind that we use is the Rhino Blinds R75 2 Person Hunting Ground Blind. Constructed of a True 150 denier polyester - 150 denier thread in both the horizontal and vertical weave.

The blind is easy to set up and take down - with a little practice setting the blind up can be accomplished quickly in as little as 60 seconds once the blind is out of the carry bag.

The blind is designed to withstand the most inclement weather conditions you dare to be caught in; rain, snow, hail, wind. The blind is treated with a durable water repellent to protect and an antimicrobial to help prevent mold and mildew ensuring you a quality product

The Permanent Blind – The permanent blind is a permanent fixture. The permanent blind is usually built using lumber or some other type of weather-resistant building materials. If you fabricate a permanent blind on your own property, or if you get permission to place a permanent blind on someone else’s property, then a permanent blind can be invaluable. Once installed, it will remain when you are not there. The animals will be more

A disadvantage of the permanent blind is that it cannot easily be moved. If the animal of interest decides to move its location, or the light is not where you want it to be the blind will no longer be beneficial. And let’s face it, most of the time you want to use a photographic blind, it will be on public or private property, where a permanent structure is not allowed.

The Temporary Blind – The temporary blind is one of the most useful. You can carry it with you and set it up wherever it is most beneficial.

Temporary blinds can be as simple as a large piece of burlap or camouflaged material like camo netting strung between two trees. It’s simple to put up, easy to carry, and takedown and can be used to blend in effectively with the local area flora and fauna.

One of the disadvantages that I have found with the temporary blind is that they are something you have to carry around with you. A temporary blind is also not good weather protection.

The Personal Blind – The personal blind is simply a large, camouflaged material that you throw over your body. A lot of people use these and have great success with them. I find it very uncomfortable to have something like a Ghillie suit on my body.

I prefer the personal blind structure like my Rhino blind.

Location of Your Blind – In order to get the most out of using a photographic blind, you have to follow that golden rule of “Location, location, location.”

How do you find the right location? I would go back to the research that we discussed earlier in the book. Look for a location near a water source. Take a hike in an area and look for tracks or other signs of activity like bedded areas in the long grass. Look for feces or skeletal remains. You can also set up a trail camera where you suspect activity. Let the camera sit for a week, then see if this looks like a good spot for a blind.

If you capture wildlife, note the times of the day and plan to set up your blind long in advance of when the wildlife was captured by your trap camera.

Tips for Using the Blind – To get the most out of your blind, here are a few simple rules you should follow.

Get to the location and set up the blind before the wildlife arrives. Pay attention to the direction of the lighting and the background that you will be dealing with. The more preparation ahead of time will help you when the wildlife shows up.

Wait in the blind until the wildlife has gone. If you want the wildlife to continue using this area you must minimize your presence in the wild.

Make the blind comfortable – You will likely spend hours at a time in it, so make it as pleasant as possible. Take bottled water and food with you and use a portable chair/seat (if you have room). You might also want to invest in a disposable urine bag with gel on the inside to soak up your urine. Seems a bit excessive, but it is important that you stay in your blind, minimize movement, and not be seen,

Minimize Movement and Sound – If your camera has silent mode I would suggest you use that. That sudden burst of photographs by the shutter is sure to startle birds and wildlife. If your camera does not have silent mode it may be best to shoot single shots and wait a few seconds between shots.

Leave No Trace – When you are taking down your blind please make sure that you pick up all your garbage and minimize your impact on the environment.

Photographing from a boat

Sometimes the only way to access certain wildlife is by ship or boat. Obviously, this is true for marine wildlife, but there are also shore-based birds and mammals where photographing from the water is the easiest or only way to see or access them. Photographing action from a moving boat presents its own unique challenges.

While on a ship, it may be tempting to bring out your tripod. Don’t bother if the engines are running. A tripod will transfer the vibrations from the engine directly to the camera, often confusing the camera’s vibration reduction capabilities. Shooting handheld is the solution to isolate from engine vibration. This same advice actually applies to land vehicles. Don’t use a vehicle for lens support when the engine is running and vibrations can be directly transferred to the camera.

Waves can also be very problematic for photography. I’ve been on a zodiac in Arctic Norway photographing orcas where the waves were rolling the boat up-and-down and side-to-side. Keeping the subject in-frame and in-focus was nearly impossible, and none of the horizons were straight. The waves even crashed over the bow and seawater ruined one of my cameras.

With significant wave action, sometimes the solution is to simply give up your photography and enjoy the wildlife. On a recent trip to Russia’s Kamchatka Peninsula, we took a catamaran to a bird sanctuary island filled with tufted puffins. Puffins in flight are extremely fast and somewhat erratic. Our boat was rolling significantly in some really bouncy seas. I attempted to photograph them, but gave up when I realized that the motion of the boat exceeded my ability to focus on the puffins and keep them in the frame.